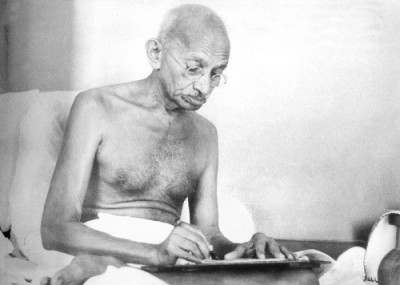

Short Story History – Riding Alongside a Mahatma

Image: commons.wikimedia.org

The newspaper in his hands read-

M.K. Gandhi’s fast enters third consecutive day in Calcutta. Doctors fear the worst.

Pranit had been coming back to read this piece of news regularly all day, ever since the paper boy rattling on his bicycle hurled the paper over the front wall in the morning. He sent the paper flying over the table and onto the floor once he was finished reading the coverage this time around. Afterwards he bent down to collect the scattered pages and then placed it on the table after arranging them in order. There was nobody around and it was surprising for eight in the evening. He came out in slow, measured steps and tried finding Gopal who, as he knew, would be out sweeping the corridors after the evening prayer. A drizzle in the evening had ensured shallow pools of water here and there and he walked around them with his trousers held up to his shins on his way to the common prayer hall.

Two men in whites were talking right at the steps leading to the hall’s entrance and Pranit could see Gopal talking to someone in there through an open window.

‘Ah Pranit!’ One of them named Mukherjee exclaimed on spotting him. ‘You didn’t attend the prayer today.’

‘I wasn’t feeling well.’

‘I thought you must’ve been to the University.’

‘What about University?’ Pranit asked.

The other man named Shankar stood with a khadi bag hung over his right shoulder and Pranit could see it full of Pamphlets that the party had planned to distribute from tomorrow onwards.

‘A group of Hindu students burned down a house owned by a fellow Muslim.’ Shankar said remorsefully.

‘It’s sad news.’ Pranit said.

‘I remember you telling me about one of your friends studying there.’ Mukherjee remarked.

‘Yes, I hope no harm has reached him.’

‘You can come along if you wish to. We were about to leave. The student wing will be present there.’ Shankar asked Pranit.

‘I’ll come if you need me.’

‘Just that you can inquire about your friend.’ Mukherjee said.

‘Not now.’ Pranit replied and then asked after a pause. ‘How is Bapu?’

‘His condition continues to be critical.’ Shankar started. ‘It keeps on deteriorating every passing hour and now everybody is concerned beyond hope. He even refuses saline water. And I was present at the rally with Panditji. I’ve never seen him so tense.’ He concluded heaving a sigh.

‘Brother, these are worst times!’ Mukherjee added eyes fixed on the ground.

They left after that. By then Gopal had stepped out in the corridor and was up to folding carpets and leaning them against the wall. Pranit came up the steps and stood by the pillar to his left and looked in the direction of Gopal, who soon noticed Pranit, finished folding the carpet which he had started and then walked up to Pranit with a smile on his sun burnt face.

‘Pranit. How are you? Did sleep help?’

‘You believe all this is going to work?’ Pranit started, not finding it important to first reply to what he’d been asked. There was no response from Gopal’s end.

‘So you’ve again started thinking about it? He asked finally.

‘It never left me.’

‘This won’t help you.’

‘Nothing seems to do that.’

‘All I can say, as always, have trust in him Pranit.’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘You are not sure of what?’

‘Of anything.’

‘Let’s sit and talk.’ Gopal said putting his arm right across Pranit’s back and walked him over to the top of steps and they settled over it. From there they could see the two men, who had been talking with Pranit, near the half open gate. On reaching, one of them, they could tell it was Shankar, pushed it open, moved out after the other and bolted it behind him.

‘So what’s bothering you?’ Gopal asked.

‘I’m not sure.’

‘Again this “I’m not sure.” If you ask me, you’re giving it too much thought.’

‘It’s this simple for you?’ Pranit asked not finding conviction in Gopal’s words..

‘No, it’s not and I don’t blame you.’

‘It…it’s not leaving me and I’m fighting hard to keep my faith intact.’

‘You’re talking like those men out there, killing each other and torching each other’s houses. I am sure at some stage or the other they would’ve said the same thing.’

‘I’m saying what I feel.’ Pranit said raising his voice a little.

‘I understand.’

‘This is what I’ve been doing all day.’

‘You were in Noakhali, right?’ Gopal asked.

‘What?’

‘In Noakhali, just a month back. You were there and didn’t you see it working there? It was difficult there as well but then it did work. All this happening today is no different.’

‘Gopal, this seems different.’

‘That is how things look at the start.’

‘You heard about this trouble in the University?’

‘Yes that and other incidents. It’s really unfortunate.’

‘All this makes me nervous and it makes me cynical.’ Pranit said and he was close to tears for his eyes went wet for a second. Just then a boy of twelve who helped Gopal with cleaning appeared and informed Gopal that someone at the main gate was asking for him. The boy said he had never seen the man.

‘All right.’ Gopal said to the boy and got up and turned to Pranit ‘You take rest. I will see you in your quarter.’ And he walked away with the boy.

Didn’t you see it working there? This is what Gopal has to say, he thought sitting there and looking at Gopal walking past the lawn, his hands brushing the boy’s head time to time. Yes it worked and I was present there to see it for myself, I was in Noakhali with Gopal and others, following Bapu all day all night long, barefoot on muddy paths skirting across that impossible terrain of the delta, across that intricate arrangement of marshes, ponds, canals and creeks, travelling from one hamlet to the other. I was there following him in his tenacious quest to put to rest the flames of communal frenzy whole of Noakhali smouldered under in those months, in part a response to the massacres Calcutta had witnessed last year. I remember and I remember it well.

Now the scene, when a footbridge over a stream had been pulled down so that Bapu’s advance towards the village located just a mile downhill after the stream could be stopped, came to his mind. He remembered clearly how the path leading to the shore, some thirty or forty metres from it was spattered with heaps of human and animal faeces and then camouflaged with layers of loose mud and thick leaved and protruding tree branches.

Alert from similar instances previously, a small team of men always walked way ahead of the main party with brooms and buckets and since it wasn’t my turn to be part of the team that particular day, closing in on the stream, from a distance we could see them squatting and kneeling down then getting up the very next moment to tie kerchiefs around their faces and bending all over again to sweep the path raising a lot of dust and we nearly lost them in it for the time we took to reach there. Once at the shore we found the bridge gone, thrashed and chopped down at both ends, a bamboo log dangling at our end and another one struggling in the muddy water. In a distance, under a grove of mango trees an anxious group of men stood looking in our direction.

Two minutes, yes that was all Bapu needed to decide he is going to walk right across the water to reach the other side. Nobody dared stopping him. He moved down the shore with somebody’s help and then stepped on the slippery bed of the stream, water reaching well over his knees. And we followed one by one, walking cautiously with slow, assured steps and holding hands and we may have well looked like strange sea creatures resurfacing over water under the evening sun, fast disappearing behind those far off hills to our left.

And now in his solitude and a cool gust of wind disturbing his hair, he recalled last couple of weeks after their return from the villages of Noakhali to this chaos and uncertainty laden metropolis. A phrase by Bapu that “Calcutta holds the key to the whole country”, practically said the moment he stepped into the city, was on everybody’s lips. Bapu believed if Calcutta is successful in conquering the air of fear and hate encircling its skies, it would prove to be a huge boost to the efforts of maintaining peace in the other parts of the country. These were the words he would then expound upon and emphasize in each of his prayer meets day and day out.

And Pranit had joined Gopal and hundreds of men and women of all age groups and from every walk of life in arranging for those grand peace rallies and prayer meetings all over the city, through those murky and pattern less network of alleys and sub-alleys in the vast slums inhabited by both Hindus and Muslims, in the campuses of every college and University with the help of various student groups and parties, on the sun beaten roads leading to city’s aristocratic residential colonies and to sprawling middle-class settlements.

Luckily, all that effort had seemed to work in their favour. Every day Bapu’s prayers were drawing huge numbers of people of every religion and it looked like city had rejected hate and insanity when, just three days back a distant spark of ghastly violence directed against a teenager, rumoured to be a Hindu kid, took shape of a blaze engulfing the whole city within a space of few hours and its people who had, till then preferred the solace of their homes thundered out with knives daggers guns clubs kerosene-bottles pistols and whichever other agent of death they could lay their hands on, and ran after each other’s lives openly in the streets.

That night, Pranit and others had wandered the roads, littered with corpses at some places and in other areas lined on both sides by houses set on fire, for some miles deserted like a trail leading to a graveyard and then for longest stretches imaginable echoing with deafening shrieks out of the madness and cruelty of one man towards the other. They wandered trying to make sure any possible help reached the needy and wounded.

At a junction Pranit’s eyes had caught a woman lying by the pavement, her face down brushing the kerb. He stopped running, letting others move ahead and pulled at the woman’s shoulder and her body turned towards him. She was there, clutching an infant in her arms and both of them had been tied together using a jute rope with several tight rounds of rope around her waist, few rounds crossing over her shoulders and a couple of them around her neck and there was a single long deep slash of a sword starting at her collar near the left shoulder, moving down across her breasts and over the baby’s skull then ending at her forearm which she had used to hold the baby. Pranit let off his hands from the body, then hurled a loud cry and the woman’s body went back splashing in the ever growing pool of blood around her.

Pranit stumbled over the pavement as he tried to get up and then rushed to join his partners, running as fast as he could. He stopped at a distance, panting alarmingly, spat few times and looked back at the woman with the infant. Somebody called his name and he started running in the direction of the call but he couldn’t go on for a long time for the blood on the streets and the cries and all the confusion heightened the nausea he was feeling. Going down on his knees under a lamp post, he threw up and then felt his head going round and round, and he heard someone calling his name, once, twice, thrice and again, and again, he couldn’t tell who it was but the cut at the infant’s head oozing blood flashed across him. There was a blast somewhere and a distant helpless cry of a woman reached him, and the broken collar of the dead woman and the slash exposing her bone at her forearm made him vomit the second time and the coughing that followed didn’t seem to rest and, and that was all he remembered afterwards, his head not going steady but spinning round and round and the shouting and people running around him.

He regained consciousness in the morning and on reaching the party office after traversing city’s ruins, Mukherjee informed him that Mahatma Gandhi had decided to go on a fast on-to death till peace isn’t restored. And that all the party members have decided to pray for him and for the cause by fasting themselves. Would he, Pranit, join them in the fast, Mukherjee had asked him and Pranit accepted not considering it for long!

Now it has been three days and things stand as uncertain as they were at the start, Pranit said to himself getting up from the steps and heading towards his sleeping quarter. If there was some break in the violence for a while then this incident at the University is sure to be a setback to any hope that had sprang up. And, what if everybody’s fear turns into reality? It is a bitter thought but who can overrule this. If Bapu leaves all of us to our fates and, and that changes nothing. I know I’m right in my apprehensions though I feel guilty about them. This wave of violence isn’t like the one in Noakhali or like the previous instance in the city last year.

The wounds inflicted on Punjab are running deep through the whole country. They run deeper, way deeper than anybody anticipated. Every day and every passing hour the tales of barbarism from its rice fields are pouring in like the burning loo hurling across the plains of North-India and it’s not letting this fire die down. One can feel the difference. Yes, all of them must be aware of this fact. Hundreds and thousands lined all along the Beliaghata Road and all those including Panditji huddled around their saint’s pallet inside Hydari Mansion. All of them! I wonder if Bapu knows it by himself. It won’t be a surprise if he does.

Inside his room the light from the bulb made his eyes ache and he’d to raise a hand in order to avoid further discomfort. Then latching the door behind him he started towards the sole window in the room which opened into an alley. He pushed it open and the wind, which had by now picked up intensity, stormed in strong and cool. Outside it was deserted and a sheet of paper, one of its edges under an abandoned shoe, fluttered helplessly. Drawing the chair closer, Pranit settled in it and looked at the night sky, bereft of clouds which would’ve caused the light shower in the evening. And the paper kept on generating a crisp, discrete sound as the wind flipped it over intermittently.

Fasting, Pranit started asking himself, how it is going to help in solving any problem. And what kind of support are we extending to Bapu this way? Aren’t we better off helping people and making a realistic effort outside than sit here all day praying, discussing things and waiting for a miracle to happen? Yes I agree it was a unanimous decision the party had taken but there had been many wrong ones taken in the past and this one, as I see it now, must be the worst of them all. There had to be some more thought given to it. Isn’t the whole idea a case of being naive in the wake of the challenges in hand? These are questions I should’ve raised that day in front of Mukherjee when he’d asked me my wish. But, but the truth is I was too taken over by the events of that horrible night to do so. Yes that is the reason and nothing else and it’s more convenient to ponder along on these lines in isolation than to do in situations like the one I faced.

But even with all this confusion in his heart and series of contradictory thoughts flooding his mind, he wished he’d been brave enough that day. It was the minimum that was required, he concluded, and then left the chair to drink water from a steel jug kept over a round table in one of the corners of the room. The next moment he was seized by a sudden, sharp pain in his stomach lasting for couple of minutes leaving him feeling weak inside and he started walking up and down the room not sure of what was to be done next. All he did was to curse repeatedly the whole idea of fasting. It was sleeping for long hours he’d been able to bear with all the trouble, physical as well as psychological, not eating for three consecutive days produced but today he’d been in bed for all afternoon and now sleep will only arrive late into the night.

The first day, obviously, had been the easiest and it was when he felt most optimistic. That day after having rested for few hours he’d visited Hydari Mansion and stayed there till the evening. With all the support and attention Bapu’s move seemed to attract, it was easier to remain hopeful. But as the day progressed, the reports of the rioting all over the city and the ever increasing number of casualties became a regular feature there. And as it approached evening a group of men brandishing swords and clubs swarmed the Beliaghata Road and hurled abuses at Bapu. They threw stones up the balcony and Pranit, hiding in a shop next to the Hydari Mansion, could hear the sound of glass panes being shattered. Somehow that trouble had been averted but all the time after that the atmosphere there, remained gloomy.

Next morning, back at the party offices, a journalist friend had briefed Pranit about the grand tragedy of Punjab and in the afternoon Pranit, standing by the parapet on the terrace, saw huge clouds of black smoke taking over the city’s expansive skyline.

Same morning he had tried reaching his family in the village over telephone but the lines were down and it continued to remain that way all day making him anxious every time he tried. Then around four in the evening Shankar stormed inside with agitated eyes, ran up and down the galleries and corridors thumping his hands at every door.

‘Come out! Out, all of you, out!’ he kept on shouting.

‘Shankar.’ Pranit had stepped out. ‘Shankar, what’s the matter?’

‘Everybody for God’s sake, I need help.’ There had been only six of them present there and once everyone was out and when Shankar seemed to have regained some stability in his breathing, he said-

‘There in front of the temple gates…Eight women, there are corpses of eight women thrown at the gates of the temple.’

‘What?’ All of them erupted at the same time.

‘Eight…and we must, we must dispose them as quickly as possible. As quickly as possible! Did you get it?’ He concluded and they left for the temple.

The women had been stripped naked and there were cuss-words carved out all over their mutilated bodies with the help of knives. Pranit had cried the whole time, cried loudly and unabashedly the whole time they performed the final rites on the bodies in an open ground. He reached back all drained out and terrified and locking himself in his room, cried with his face in the pillow till he fell asleep.

And today had been a maddening day as well, a day marred by a sharp decline in his physical strength and a day making him feel that his worst fears will turn into reality. He’d experienced regular blackouts since the morning and remained tortured by a severe headache till a nap in the afternoon put a rest to it. Now, sadly he was again going through all that after a brief respite. It’s too much to ask from anyone, he thought. I don’t think I’ll be able to stand it any further. It looks way beyond my reach. Or, the next moment he asked himself, should I stop thinking on these lines? Maybe Gopal is right in this too. It’s quite possible.

Once his mind went calm with some difficulty he tried recalling the life he had lived before deciding to be a part of all this. He’d just completed his matriculation after two failed attempts when Gandhiji called for the Quit India Movement. It was such a glorious time, he thought. He envisioned Calcutta of that period, still clear in his mind like a sunny day in March. Calcutta bubbling with nationalistic fervour at every nook and corner, and Calcutta of month long rallies with shouting of forceful slogans and brandishing flags and banners, Calcutta full of hope of nearing that much awaited dawn of independence and most importantly Calcutta devoid of this madness, this fear and this incessant bloodshed.

He replayed the argument he’d had with his father after announcing at home his desire to join the national movement, preferring it over higher education which his father proposed. It was the first time he’d taken a decision for himself and it, as he realized, was not a bed of roses. And he remembered the silhouette of his mother against the first rays of the day when he left home that early morning with some like minded fellows from the village. He could never get that image out of his mind after that and he’d always tried to imagine the plight she must’ve gone through. But she never said a word. Not a word!

Thinking about mother is a pleasure at such a conjuncture in life, he said loudly. Thinking about her is a pleasure guaranteed for all the times. But closely following is loneliness emerging out of the realization that you can’t be with her anytime soon.

After three days he’d found his mind taken over by a nice idea, idea about his mother and his life in the village, and he didn’t let his mind wander for some time. It was too precious a moment for that and he felt relaxed awhile. Then, as if beckoned by a heavenly voice, he rushed to the table, grappled inside a small drawer and eventually taking out a pack wrapped inside a newspaper sheet. He pulled out the ends of the paper with a series of swift hand movements to undo the contents of the pack. Two slices of stuffed bread! Yes, two slices of bread he’d furtively arranged in the morning in a similar moment of ideological and spiritual weakness.

But is this the only way out, he asked himself not taking his eyes of the bread in his hand. It’s easier to succumb to your fragile senses in a struggle like this than to hold back and brave the storm. This is how he’d always motivated himself and it had carried him this far, way beyond the initial dream of his country’s freedom. Yes it has been the reason and nothing else. But what is going to happen to him if he goes forward with this, if he forgets everything for a moment and devours on this bread? Is something due to change? Will it make him a lesser man or will it undermine whatever little contribution he had made being a member of the party? No, definitely not. Then what makes me think so hard, what is so difficult? It has to be something. Can anyone tell with absolute conviction that everybody has been honest and sincere in their vows to fast, that nobody has cheated their Mahatma? Nobody can do that!

It’s not any fancy doubt, he continued thinking. It makes sense. It does. Nobody can be sure for there is no way to determine it. I’m sure all of them have suffered the way I have and everyone has questioned himself the way I’ve been doing for the last three days. Then why not? Why not? Why isn’t it possible? It is and it hasn’t made any difference to anything. Everything remains intact, same, without even a feather touch of change. This whole place with its lugubrious evening prayers and pointless discussions, the savagery on the streets, thousands being butchered in the name of religion in Punjab, that reprehensible sense of gloom around Hydari mansion, Panditji’s extraordinary concern for his Bapu, and Bapu’s dream, all remain the way they were, without a feather touch of change.

Yes Bapu’s dream is still a dream and ask anyone, anyone you may find who has set foot in the streets of this Godforsaken city in the last three days and he’ll tell you with a chilling frankness that Bapu is hoping for impossible, that Bapu curled on his pallet with a frail body and colossal spirit, for the first time in his life, is harbouring wrong notions about his countrymen, that his life and death makes not an ounce of difference to the masses that have gone mad out there. Ask anyone, he’ll tell you!

And yet Bapu is immovable, he cried out with tears in his eyes. Mahatma, that great soul to the millions is still holding on to his fort against all odds. But he forgets, as he says his hymns this evening that people behind him, ones following him unconditionally are no great people but are only being led by a great soul, that those ones have neither the insatiable courage he possesses nor the unshakable belief in love for humanity which he radiates in each of his actions. Probably this very greatness is behind the biggest and most lamentable tragedy of his life!

By then, not a loaf remained of the bread. He followed it with drinking a lot of water and throwing the paper out of the window. Just then there was a knock at the door, a hard, excited series of knocks followed. It was Gopal.

‘Pranit, Bapu has ended his fast! Pranit Bapu has ended his fast.’ He hugged Pranit tightly and laughed out loud and there were tears running down his cheeks.

‘Shankar says trucks full of grenades, pistols and other weapons were voluntarily given up at Hydari House by hundreds of hoodlums and trouble makers. All of them were present, all of them…Hindu, Moslem and Sikh leaders…all of them were there and they have pledged in front of Bapu that, that communal strife won’t strike Calcutta again! Can you believe it Pranit? I told you, you remember I told you to have faith in Bapu? Didn’t I tell you that? There has been no violence for hours now, nothing. Isn’t it…I told you so!’

__END__

Author’s Note:

On 1st September, 1947 Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi announced his fast on to death in the wake of the sudden break out of violence between the Hindu and Muslim communities of Calcutta. It was 73 hours after that, on 4th of September that he broke the fast after a pact was decided upon by the warring parties. Peace returned to the city and was never shattered again in Gandhi’s lifetime; an act of heroism which many believe remains his greatest achievement.